I would have liked to have met him, in person, in other circumstances. To have learned more about the man who, as a child, I watched on television during his tours of agricultural or sugarcane production sites. The man who Fidel resembled so much in his expressions, his features. Life had now brought me to an address in Siboney, where his presence is felt on every corner. A friend and compañero of his - Dubermán Acosta Filgueira – showed me to his home, where I met one of his daughters, Lina, in the street in front, with tears for words and whose face expressed her pain.

Trying to compose herself enough to speak, she accepted the respectful and heartfelt request from someone she did not know, and led me to the room where her mother was, surrounded by close friends, family and people who needed to express the first “hasta siempre” to a man who did so much for his country.

His wife Alicia’s hand clasped mine, and the sadness she was trying to silence hit me harder, as I stood there beside her. She had been his secretary for 54 years and loved him for many more.

How to talk of Ramón Castro Ruz without seeing him through the eyes of his family? How to write about “Mongo” Castro without drawing on the testimony of those who knew him up close, just as he was, as he will continue to be. And I found myself faced with the obligation not to let all those anecdotes be lost without putting them onto paper, and promised myself that they were owed, at the very least, a book.

Alicia - drawing strength from the image of her husband just a few meters in front of her, before which many of those who cared for him had passed – spoke to me of a love of another era, like that of fairytale. His compañera in so many senses, and his secretary at work for several decades, she described the father, husband, grandfather to me. The early riser, up at five every morning, even when it wasn’t necessary. She talked about projects, so many works with his personal stamp but for which he never claimed any credit, and in a few minutes she had recounted a life together in anecdotes that could fill a whole newspaper.

She told me of one of the car journeys they shared, when Mongo stopped to give a woman a ride. Even though she was headed far out of their way, he decided to take her where she was going. He would explain later: Alicia, you do someone a favor properly, or you don’t do it at all. The same lady confessed to his wife – “He does not remember me, but he’s given me a ride four times”. That’s how unassuming he was.

Speaking to Granma, Frank Alejandro Bernabeu, a close friend of Ramón’s, illustrated other aspects of the man, beyond the public persona. He spoke with sentiment about his solidarity, “the exemplary marriage” he nurtured, his playfulness, his friendly nature. He recalled Mongo’s time in prison after the attack on the Moncada barracks, and that he was a major supplier of the Second Front. He made it clear, through many experiences, how he earned, by the sweat of his brow, the title of Hero of Labor of the Republic of Cuba.

At this point Alicia intervened, to tell me that Fidel, being his brother, wasn’t very comfortable with awarding him the recognition. But eventually the proposal from the Cuban Workers Federation materialized – which was more than fair – and it was put to other greats to decide. Blas Roca, without hesitation, raised both hands in approval and was followed by others in resounding agreement.

Among his wife’s most treasured memories are those of him taking on the problems of others, at any time day or night, and his vocation for thinking up the best way to help them. In my journalistic attempt to describe him, aiming to be true to his personality, she interrupts me: “Look at that face, that kind face,” and points to the image on the wall in front of us, behind a flag covering the urn containing his ashes.

Another friend, who spent more than thirty years by his side, following his example and in his footsteps, responds to my question with another: “What more can I say about Ramón? Just imagine. He was exceptional. An incredible person.

Minutes beforehand, Dubermán, in his home in Santa Fe, had mentioned this quality of the second child of Don Ángel Castro and Lina Ruz, the oldest of their three sons, of making an impression due to his innate sensitivity to the problems of others, which he considered as if they were his own. Which he made his own. He recalled the educative nature of someone who, in many senses, he considered a teacher. “Ramón was always a teacher to me.” Recognizing his inability to speak of him in the past tense, he continued, “He is an open book. A man of the people.” And between involuntary biting of his lips, due to the emotion, he spoke of his main contributions to the sugar industry and agriculture, and his wealth of “natural wisdom.”

A deep humanism is a recurring theme in Dubermán’s stories - the rides he offered during his frequent trips across the country, dedication to his work, “living in a trailer with his wife and small daughter” during the times of the Valle de Picadura plan (Ramón was deputy director), all those Sundays he dedicated – during three consecutive years – to voluntary work.

He recalled an image of Ramón atop a Komatsu bulldozer. Someone brought him his lunch, but he didn’t get down from the machine, instead he ate hurriedly to continue working. “To see him work that way really impressed, it moved people,” he confessed. Looking into the distance, he continued, “Even more so because he had no need to do so, but he did it from the heart, he was moved to.” Between tears he revealed the greatness of his boss and friend in a single comment: “He didn’t hide behind his surname or his history; he earned his merits himself. Faultless,” he concluded.

Fidel Ruz, a founder of the Valle de Picadura plan, summarizes Ramón’s nobility in a single anecdote, with the spontaneous eloquence that is natural to someone from the countryside. He was twenty-odd years old back then – he’s lost count now aged 82. He recalls that Mongo managed his parents’ farm at the time. As soon as any worker or neighbor – especially the poorest – got sick he would put them in a car and take them to the closest hospital, reassuring them with the phrase, “The old man is paying, save him.”

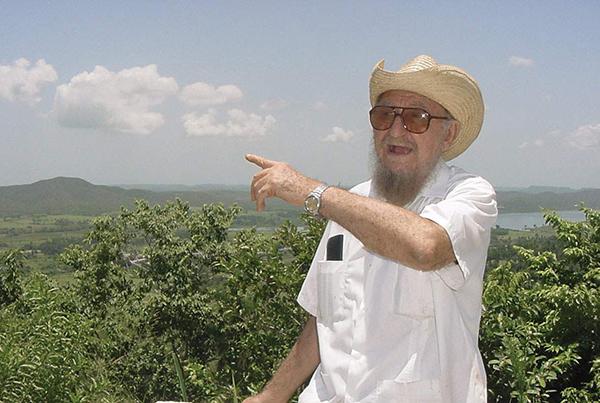

“Dressed in his traditional white guayabera, his cloth hat and with an unlit cigar between his fingers,” is the image that sticks in the memory of the oldest of three brothers, Alcides López Labrada, general director of the Minag Training Center, who back then was the Agriculture Ministry’s delegate in the province of Havana.

“At first glance, and from afar, his personality left an impression, especially due to the striking resemblance between him and Fidel, but when one approached him, you immediately discovered a friendly nature, his modesty and generosity. He was a natural man of wisdom. He possessed great expertise, not exactly acquired from the academy, but through hard work and the direct link with nature, the land, plants and animals, first on his father’s farm in his native Birán and then in the tasks of the Revolution that Fidel himself entrusted to him. The first and most difficult of all, involved the family’s land. But undoubtedly his most important work was the construction and management of the Valle de Picadura Special Plan,” Alcides affirms.

“In each place he visited,” he continues, “he could not fail to mix with 'the people from below.’ Immediately, timely revelry and contagious laughter would ensue. From the women he asked for three kisses: one for Fidel on the forehead, and one for Raúl and his own on each bearded cheek. He challenged the men to arm-wrestle. He really had a lot of arm strength. He spoke of a 'concoction' his wife Alicia prepared for him in the mornings, made from various liquified vegetables. 'It tastes bad, but it keeps me strong and healthy,' he used to say.”

However, Alicia tells me that her husband liked the “concoction” she lovingly prepared for him, consisting of a cocktail of highly nutritious vegetables including parsley, celery, carrot, cucumber and spinach. “Give it a try” she offers.

“On one occasion, Lázaro Toledo, an old revolutionary from the area, who at the time was municipal delegate for Agriculture in San Antonio de Los Baños, and who also thought of himself as a Roman gladiator, accepted the duel. My gestures asking him to give up were to no avail, until making use of my authority, I had to signal to him to loosen his grip because otherwise, one of the two would be injured. After publicly declaring Mongo the winner, the two shared a poignant embrace,” Alcides recalls.

Returning to the great similarity between Mongo and Fidel, he repeats a phrase which all my interviewees referred to: “It’s not me who looks like Fidel, it’s him who looks like me, because I’m the oldest.”

And as we near the end of what is more like a chronicle than a simple interview, Alcides pauses, as if looking at a portrait, “His nerves and muscles exuded the desire to work and engaged the enterprising. Witness to this were the Genética del Este company and the cattle ranchers in Ariguanabo, Oeste, and el Cangre. In the latter, one Sunday morning we took him to see a Komatsu towing a ‘Vanguardia’ (Cuban made tractor) – an implement dreamed up, invented and built by him for clearing marabou without affecting the soil.

“He was so delighted that, despite his advanced age, he asked to operate it, climbed up on the machine, and spent more than an hour cutting down weeds and singing Mexican songs. When I tried to ask him to get down so we could continue and avoid a crash, he said: ‘Jump on so you live this experience'. Thus was this Don Quixote of the Cuban fields.”

Without giving me time to fully appreciate this last phrase in all its magnitude, which served by way of a title for this piece, he made another poignant observation: “He was a happy man, because he also contributed his part to the construction of this great collective work.”

Julia Muriel Escobar, Minag cadre director, sitting in her office shortly before an urgent trip, assures me that Mongo Castro had “a deep love for agriculture. The kindness, tenderness that overflowed in his gaze and in his speech, the affection in his greeting...and at the same time, the strength of his hands. An exceptionally loving and tender human being, with a family in which there was always love and a friendly atmosphere. Thus he lived until his very last day. Our agriculture has no way of paying Mongo for everything that he did.”

To this portrait made of memories, constructed by several voices, speaking from the heart, I add just one observation: Cuba, the ground beneath our feet, we have no means of paying the man who nourished us from his humility, the healthy pride he felt for his brothers, and that they – in actions more than in words - also felt for him. Ultimately, Mongo knew very well how to cultivate his own greatness.