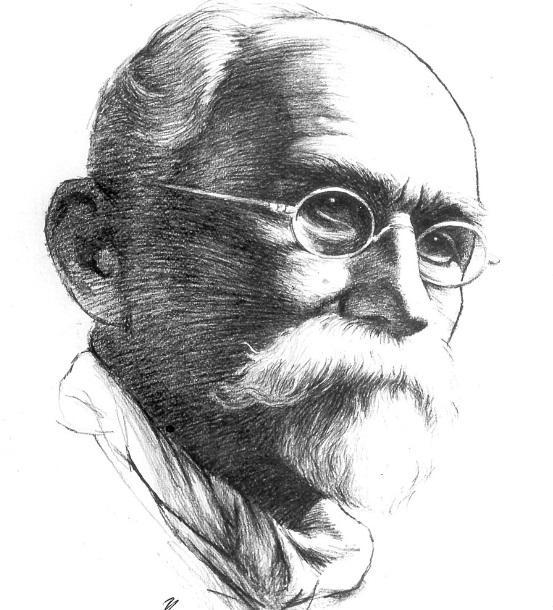

Not even dedicated entirely to him, this edition could cover the human, political and military dimension of the man who was born on November 18, 1836, in Baní, Dominican Republic, and later devoted himself completely to the independence of Cuba, where he became General in Chief of the Liberation Army.

The synthesis around Máximo Gómez Báez can mediate between the almost impossible and the unjust, since he joined the Dominican army at the age of 16; or when, already in Cuba, he conspired in the area of El Dátil.

His uprising, his promotion to Major General by Céspedes, his first machete charge as a terrifying prelude to the enemy.

I am talking about the man who, removed from command in 1872, due to a misunderstanding, later assumed new responsibilities: he reorganized troops in Camagüey and Las Villas, and refused to join the movement to remove Céspedes as President.

Exile, dreadful family misery in Jamaica, farming in the bush to survive, imprisonment in the Ozama Fortress (Dominican Republic) for conspiring in Cuba... nothing could break him.

I can imagine José Martí when, upon being asked to assume the military command in the future conflict, Gómez replied: "From now on you can count on my services". And then, the Manifesto of Montecristi, the landing at Playita de Cajobabo, the Invasion on horseback and machete in fist, the epic crossing of the Path de Júcaro to Morón: impregnable according to the Spaniards.

Brilliant was that loop when, in apparent flight, it retreated a few kilometers to attack in an enveloping advance towards the West, destroying railroad lines and enemy communications.

The Spanish generals in Havana were disconcerted when they avoided open combat, took refuge in mountain cays and reappeared in the rear, with brief and fulminating actions.

The pain of the fall in combat of Antonio Maceo and his beloved son Panchito was irreparable. But it continued, even after the fateful end of the war; because Gómez is still Gómez.

In his essay Porvenir de Cuba (Cuba's future), he would expose: "... and there we have the Platt Law, eternal license turned into obligation for the Americans to interfere in our affairs."

Clear, unbending, he suggests the creation of the Cuban Militias, with some 15,000 men that would make "the intervention of American troops and the Rural Guard itself unnecessary."

On June 17, 1905, he closes his eyes, convinced that "on the ground soaked with so many tears and blood, only one flag should fly, the one that protected the sacred ideal of the Homeland."

Truly, the man who one day said: "My degrees, my political significance, truncated in solemn moments of history, my glories cut off and all that is worthless, it is ephemeral, but no one can ever deny that I was a loyal soldier of the freedoms of Cuba. That's enough for me and I don't want more."