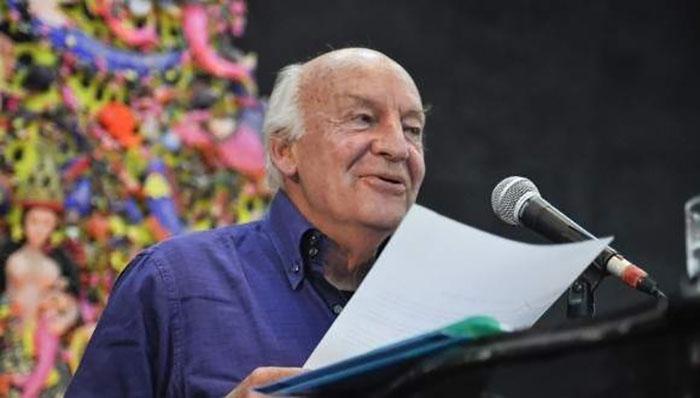

Following the death of Eduardo Galeano (Montevideo, September 3 1940-April 13, 2015), emblematic figure of Latin American literature, two of his writings stand out as visionary on this tragic occasion.

The first that comes to mind is the thought he expressed last year on the death of the Nobel laureate, Gabriel García Márquez, and which now seems appropriate for himself: “There are pains which are expressed through silence. They speak silently, but they hurt just the same. How the death of Gabo pains us… Yet he goes on living as long as his words live and laugh and speak.”

The second reference must be to The Book of Embraces, a collection of 191 brief texts published in 1989, which resembles the Bible, passing from the beginning of the world to a kind of apocalypse, and entails critical thinking about human reason, memory and forgetfulness.

From this singular book we take the chapter entitled, Weeping, for the author:

“This happened in the jungle, in the Ecuadorian Amazon. The Shuar Indians were crying over someone’s dying grandmother. They were sitting by her deathbed, crying. An observer from another world asked them:

“Why are you crying in front of her when she is still alive?”

And the ones who were weeping responded, “So she knows how much we love her.”

Galeano knew it, writers must be read. That’s why we need to return to The Open Veins of Latin America, the essay in which he compiled an “accessible and disturbing” history of Latin America, as Mexican author Elena Poniatowska put it.

The Uruguayan wrote with simple words and a touch of irony, and that was his secret. He had said in 2004: “I am a hunter of stories, a listener of voices,” and in 2012 – on presenting his book, Children of the days, in Madrid, which brings together 366 stories both from known and anonymous sources, one for each day of year – “I seek...a non-formal language to think, feel and enjoy…”

So the reader finds in The origin of the world, in The Book of Embraces:

“The Spanish War had ended only a few years back, and the Cross and the Sword reigned over the ruins of the republic. One of the defeated, an anarchist worker fresh out of jail, was looking for a job. He scoured heaven and earth in vain. There was no work for a Red. Everyone looked daggers at him, shrugged their shoulders and turned their backs. No one would give him a chance, no one listened to him. Wine was the only friend he had left. At night, before the empty dishes, he bore in silence the reproaches of his saintly wife, a woman who never missed Mass, while his son, a small boy, recited the catechism to him. Some time later, Josep Verdura, the son of this accursed worker, told me the story. He told me in Barcelona, when I arrived there in exile. He had been a desperate child who wanted to save his father from external damnation, and the ever atheistic and stubborn fellow wouldn't listen to reason.

“But papa,” Josep said to him, weeping. “If God doesn't exist, who made the world?”

“Dummy,” said the worker, lowering his head as if to impart a secret, “Dummy. We made the world, we bricklayers.”

Andhow doesGaleano view The world inthis same book?

“A man from the town of Negua, on the coast of Colombia, could climb into the sky. On his return, he described his trip. He told how he had contemplated human life from on high. He said we are a sea of tiny flames, “The world,” he revealed, “is a heap of people, a sea of tiny flames.”

In To Be Like Them and Other Articles, published in 2007, he refers to literature and new technologies, “I wonder: Is there still a future for literature, in this world whereallchildren aged fiveare electronicsengineers?And I would liketo answer myself: Maybethe lifestyleof our timesis not thatgood for people, or nature; but it iscertainly very goodfor the pharmaceutical industry. Whycouldn’t italso be verygood forthe literary industry? Everything depends on theproduct offered, itmust betranquilizinglike Valiumand shinyandlight, like on a TV show: to help usto neither think with risk or tofeelmadly,to avoid dangerous dreamsand above allavoidthe temptation tolive them.But it turns out that'sexactlytheliteraturethat I am notcapable of writing or reading.”

Each Latin American country has expressed dismay for the death of Eduardo Galeano, and in Cuba, with whom he maintained a fond relationship, there were many expressions of sadness.

The President of the Councils of State and Ministers, Raúl Castro Ruz, sent a message to his Excellency Tabaré Vázquez Rosas, President of the Eastern Republic of Uruguay in which he said:

“Esteemed President:

It is with deep regret that I have learned of the death of the outstanding revolutionary intellectual and beloved friend of Cuba, Eduardo Galeano. I extend my most heartfelt condolences to the family of the unforgettable Galeano and the Uruguayan people he so worthily represented.”

At the Casa de las Américas his inaugural speech for the 53rd edition of the Casa de las Americas Prize for Literature in January 2012 was recalled: “Errata. Where it says: October 12, 1492, it should read: April 28, 1959. On this day in April the Casa that has most helped us to discover America and the many Americas that America contains was founded in Cuba [...] This Casa is my casa...”

Galeano won the Casa’s Novel Prize in 1975 for Our Song and the prize for testimony in 1977 for Days and Nights of Love and War. In 2011 he received the José María Arguedas Prize for Narrative for Mirrors. Stories of Almost Everyone.

The National Union of Writers and Artists of Cuba (UNEAC), which granted Galeano the title of Member of Merit in 1998, expressed its “deep dismay” over the death of the Uruguayan intellectual.

In a statement signed by its President, writer Miguel Barnet, it was noted that Galeano was “a spokesman for the just causes of humanity,” and “He knew how to do this with great intellectual ingenuity and literary beauty.”

We must mourn Eduardo Galeano so he knows how much we love him, and we must read him so that his words “live and laugh and speak.” •