Great photographers have always captured important moments in time and space. The role of photo-journalists has been critical to the recording of historical events, while at the same time, photography inhabits two worlds, that of technology and that of art.

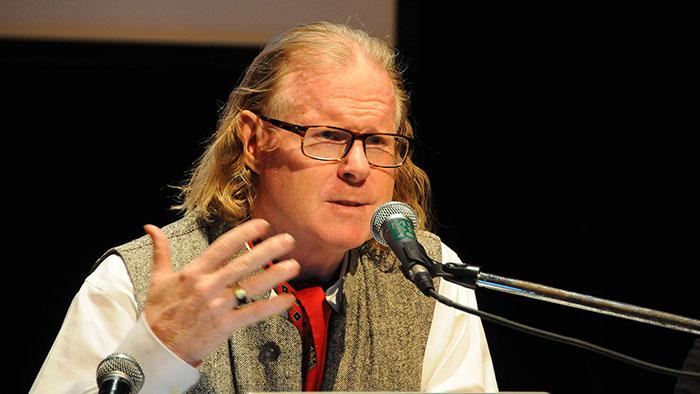

The personal exposition of U.S. photographer Peter Turnley (Indiana, 1955), one of the world’s greats, in the Cuban Art building of the National Fine Arts Museum, eliminates any doubt regarding the classic question: Is photography art?

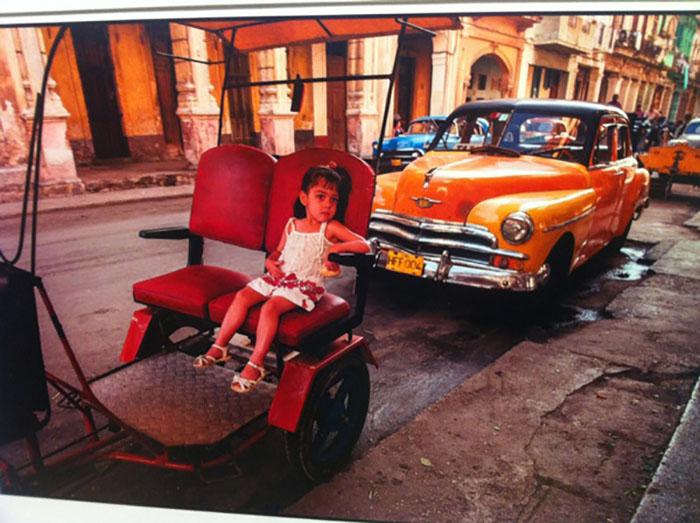

Every item exhibited stays with viewers, and with Moments of the Human Condition, Turnley has captivated more than 35,000 visitors in Havana. His photos reflect the author’s very own, inquisitive, honest view of dissimilar events which occurred in the more than 90 countries he has visited over the past 40 years.

Niurka Fanego, head of the Fine Arts Museum’s department of collections and curating, explained that the show was organized as a retrospective, an anthology of the artist’s work, which has been published in media such as The New Yorker, Newsweek, National Geographic, Life, Le Figaro and Le Monde.

Moments of the Human Condition includes 130 photos, grouped in four sections: The heart of America (the socially excluded in the U.S.); Love letter to Paris (street scenes); In times of war and peace (refugees around the world and other historic moments), and Cuba, A grace of spirit.

Turnley has generously donated 20 of these impactful shots to the National Fine Arts Museum, that is to the National Patrimony, including Fall of the Berlin Wall, 1989; Kosovar-Albanian refugee, 1999; Midwife. Bukhara, Uzbekistan, 1987; and Havana’s Malecón, 2015.

It has already been said that Peter’s Turnley’s journalistic work is extensive, spanning several decades, and he offered a master class on this specialty, February 16, to close the exposition which opened on November 13, 2015. To facilitate the reading, I am reproducing some of his ideas, and his replies to queries from participants, in a question and answer format.

Photography in general?

The photo itself has enormous impact on those who see it. The act of taking the photograph is a revolutionary act for me. It is always about sharing the moments I have decided to frame, those which represent feelings, perceptions, observations of the world that surrounds me, be they moments we admire or that we denounce.

When did you begin?

At 16 years of age, I started to take pictures in Fort Wayne where I was born, and I realized I could talk to people with the camera, and it gave me the ability to communicate my feelings. I quickly understood that the camera gives you power, because it gives you a voice, and it can also give those who are not always heard a voice.

Studies?

I never studied photography. (He graduated from the University of Michigan, the Sorbonne, and the Paris Institute of Political Studies.) I went to Paris in 1978 and started with street scenes. In 1981, I was Robert Doisneau’s assistant (another great associated with the French school of humanist photography.)

I was inspired by the work of Cartier-Bresson (considered the father of photo-journalism.) He said that more important than one’s command of technique is knowing the human condition, history, art.

What attracted you to photography?

What has most interested me, around the world, is seeing how similar all people are. I am not a great believer in borders; I think we are a big family, humanity. What’s the worse for me? Ignorance that leads to intolerance.

The most significant moments?

The fall of the Berlin wall, the end of the USSR, being in New York on September 11 of 2001, and photographing what is now known as Ground Zero, and the devastation caused by hurricane Katrina in New Orleans. The most beautiful was seeing Nelson Mandela released from prison, after 27 years and the end of apartheid.

You have declared your love for Cuba…

I come from a progressive family. In the 60s, young people around the world began to question authority, for example in France, and in my country, they marched against the war in Vietnam and for civil rights. When I came to Cuba for the first time in 1989, during Gorbachev’s trip, I saw a society that in many ways provided answers to what many of us had dreamed. When I travel, I feel the need to tell the truth, what I see. Here, I immediately saw a country and a people with great grace, dignity, spirit, and marvelous humanity. Since then, I have come back more than 30 times. This exposition is one of the greatest honors of my life. It’s very important for me to be here in Cuba at this historic moment.

Objectivity?

I don’t know what this word means. When you hit the shutter is a decision you make. But I do know what honesty is. I reject the folkloric, the touristic, to immerse myself in the unspeakable, the authentic. I do what I feel in my heart is correct.

The photo-journalist today?

The profession of photo-journalism changed, above all, with the arrival of the digital age. Before, you had to return with the picture. Now, you can send a photo from Afghanistan to the United States, for example, in 30 seconds. The dynamics have changed a great deal. I don’t see it as something negative. The Internet has democratized the image, and this is positive if you agree that photography is about sharing.

Peter Turnley has shown his Moments of the Human Condition in Havana, and a few months ago published Cuba: A Grace of the Spirit, 130 photos taken over his 30 years of visits to the island. His declaration of love.