A few months ago - before we were hit by COVID-19 - I read a travelogue about Cuba, written by a certain writer born in our country, now living abroad, who confessed that he was rediscovering the island after several years of absence.

For a couple weeks, he traveled from east to west and back, leaving us five pages full of words like santero, palma real, daiquiri, mulata, asere, balsero, frutabomba, jinetera, yucca with mojo, picadillo de soya, cucurucho de mani, amarillos and pan con pasta.

The chronicle sounded like Cuba, but it was not Cuba. The reading reminded me of the first voyage made by Columbus, and when, upon his return, he appeared in court with naked natives, covered with colorful feathers and tattoos; in one hand a spear and in the other, a parrot that shrieked words in Spanish.

I also recalled the surprise Borges reported upon reading Gibbon's observation in his History of the Decline and Fall of the Roman Empire, "In the Koran, the Arabic book par excellence, there are no camels."

Of course, there are. I have a copy of the Koran in PDF format, and, by means of a search engine, was able to find the word on page 40. The detail, however, does not detract from the concept. If a western tourist were to write a chronicle about visiting the Arab world, they would not fail to lavish caravans of camels on every page. Muhammad, on the other hand, knew that he could pass for an Arab without mentioning the word.

One thought always leads to another, and suddenly it occurred to me to investigate - using the same search engine - several authors who critics and tradition point to as being among the most representative of Cuban literature. I dug into Carpentier and Lezama's emblematic books: works full of characters defined by their dreams, hopes and existential conflicts; but in these works I did not encounter a single peanut or papaya, or any of the items that are customarily used to stereotype Cubans.

If we agree with Fernando Ortiz that “cubanidad” (being Cuban) is "a condition of the soul, a complex of feelings, ideas and attitudes", while “cubania” is "full, felt, conscious and desired Cuban identity; responsible Cuban identity", then it is obvious that both terms imply ways of being that cannot be touched with the hand. They are transcendental, derived from being, not from having; characteristics that go beyond and dialectically surpass the material world. It is amazing that Marti, at the age of 16, already had a clear conception of this idea.

While I was reading the reference chronicle (which is really just a sample of many others, including stories and novels that peddle and auction off pseudo-Cubanisms in identical markets) I also wondered: What elements united our most distinguished writers when this blessed land called Cuba stopped being simply "the grass on which our plants tread," to become the collection of sentiments that underlie the word homeland?

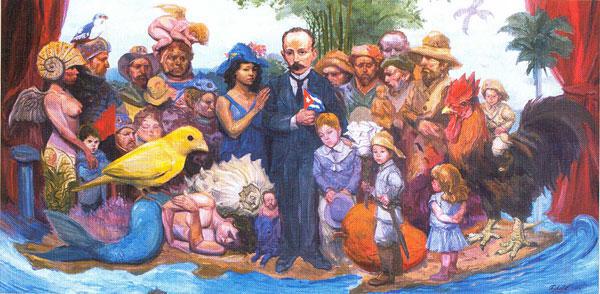

During the 19th century we had notable poets from different social classes and layers, some of them strongly opposed: a son from a rich home like José María Heredia, another from a poor one like José Jacinto Milanés, a black slave like Juan Francisco Manzano, a free mulatto like Gabriel de la Concepción Valdés, a so-called homemaker like Luisa Pérez de Zambrana, a rebel like Gertrudis Gómez de Avellaneda, a country boy like Juan Cristóbal Nápoles Fajardo, a young city dweller like Julián del Casal; a being, on whom mixed feelings weigh, like Juan Clemente Zenea, and an impeccable patriot, of universal thought, like José Martí. What hidden essence united this diverse group? Obviously, not a "ridiculous love for the land;" they were linked by an emerging feeling of Cuban identity; the embrace they together gave the homeland.

Now then, since Cuban identity is "responsible Cuban identity", on October 10, 1868, a group of men rose up in arms in search of full Cuban being, "desired and conscious" Cuban identity. It was no longer a question of exercising the condition based on a desire or simply habit, suddenly a feeling of devotion had emerged (a term I do not choose at random, but because it expresses the action of giving oneself body and soul to the sacred). The story is known, I will not repeat it; with this mention I only wish to emphasize that this identity cannot be contemplative or pedantic; it implies a taking of sides, based on specific principles, specific values.

I would also like to assert that if Cuban identity is a substance that fertilizes love for the homeland, adulterating it or exploiting it for profit, in the most innocent of cases, is simply negating it.

Martí said: "Homeland is humanity, that portion of humanity we see closest to us and in which we were born;" and this is an evident expression of consistency. But what is human? Is it that which makes a caricature of our ways or reduces us to curious magpies that, given their habit of collecting objects, occasionally store things that are not at all shiny? Or is it that which dignifies and uplifts to high levels of justice, knowledge and love for the human condition?

Extracted from its broad connotation, the phrase "Homeland is humanity" has often been cleverly presented as a call to dissolve into the ambiguous the affection we have for this “portion of humanity in which we were born.” It has also been used as a deceptive weapon to discredit and disregard the idea, when it continues to be viewed from a perspective of alienation and bad faith, with the clear objective of eroding the values, symbols, beliefs and dear sources of pride that comprise our cultural identity.

Certainly, the day will come when humans will be one people, but that global culture cannot be built on the ruins of what we are.

Cubania is responsible Cuban identity, Ortiz says, and then adds that it possesses “three virtues, theological concepts: faith, hope and love." What I mean to say is that the issue is not about renouncing critical thinking or human improvement; nor is it about viewing ourselves as modern Narcissuses in the water of self-glorification; but, returning to Martí: "Language is but smoke when it does not serve to envelop a generous feeling or eternal idea."