The triumph of the Revolution, in 1959, was an event of overwhelming social scope in Cuba and, by extension, also of high impact on art. The previous neocolonial governments of the time, corrupt, pro-imperialist and insensitive to the aesthetic demands of a people whose access to culture at that time was only focused on their wealthiest strata, were never interested in cultivating the spirit or the artistic education of the different social classes.

The marvelous whirlwind of the new social process changed the rules of the game by allowing Cubans to educate and instruct themselves. On that road, it was a cardinal premise that they should know the different manifestations of art and, in order to achieve this, it was necessary to create entities or institutions to support their projects, financing and lines of development.

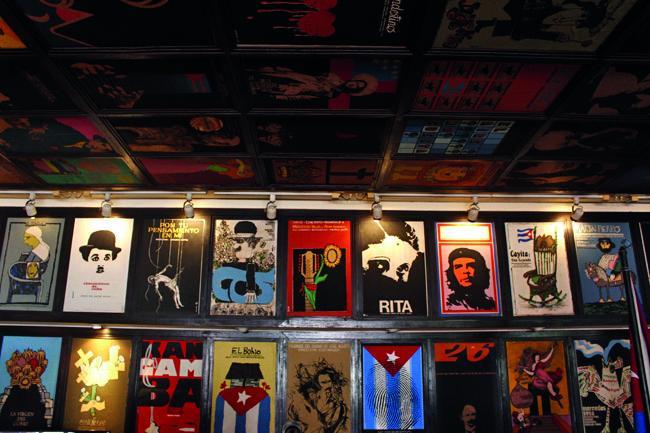

Through the foundation of the Cuban Institute of Cinematographic Art and Industry (Icaic), under the direction of Alfredo Guevara, in 1959, the possibility of creating on the island a cinema understood as the most powerful and massive means of artistic expression, as the most direct and widespread vehicle of education and amplification of ideas arose.

Thanks to Icaic, documentary and fiction films took off with great force, practically in unison. The early 1960s was a special scenario, both qualitatively and productively, for the nascent revolutionary screen.

The national cinema of the decade knew the creative power (it was the most outstanding authorial moment of both careers) of two masters of the seventh art, not only on a national scale, but also universal, as Humberto Solás and Tomás Gutiérrez Alea, who in the decade made those two unfading pieces entitled Lucia and Memories of Underdevelopment germinate.

From then until today, the Cuban screen has been enriched, and continues to do so in permanent evolution, thanks to the work of essential creators such as Julio García Espinosa, Santiago Álvarez, Manuel Octavio Gómez, Sara Gómez, Sergio Giral, Manuel Pérez, Octavio Cortázar, Pastor Vega, Juan Padrón, Enrique Pineda Barnet, Juan Carlos Tabío and Fernando Pérez, among many others.

The Cuban cinema of the 21st century would receive the fresh blood of new filmmakers, with unprecedented thematic-genre paths. Despite its economic limitations and some titles released without much artistic or even commercial sense, so far this century the Cuban screen has produced an outstanding production, marked by the opening to new plot scenarios, the green light to brand-new projects and the materialization of valuable ideas.

Cuba Libre (Jorge Luis Sánchez, 2015) and Inocencia (Alejandro Gil, 2018) have been the two best expressions, in this century, of a solid historical cinema, about events of great importance in our past, made visible to the new generations through well-designed stories. It is a genre that needs to continue to be filmed.

To its glorious history, Cuban cinema -a true conquest of the Cuban Revolution; as is, of course, Icaic, its pillar and fundamental support- still has a great future to add.