French President François Hollande was quick to comment on the recently concluded financial negotiations with Greece, saying that nothing could have been worse than humiliating the country when it comes to the issue of repaying its enormous foreign debt.

If the outcome was not humiliating, many are wondering how to describe the fact that Greece must now submit its economic policies to foreign financial bodies for approval before they are considered by the nation’s parliament.

Or how to understand the requirement that, in order to receive a new rescue plan of 50 billion euros over three years, Greece must now sell hundreds of public properties; reduce salaries, jobs and pensions; increase income and value-added taxes, among other draconian measures, in a nation with an unemployment rate of 27%.

In return the sacrosanct European Union (EU) agreed only to restructure repayment of the country’s foreign debt, without reducing by a single euro the astronomical amount owed.

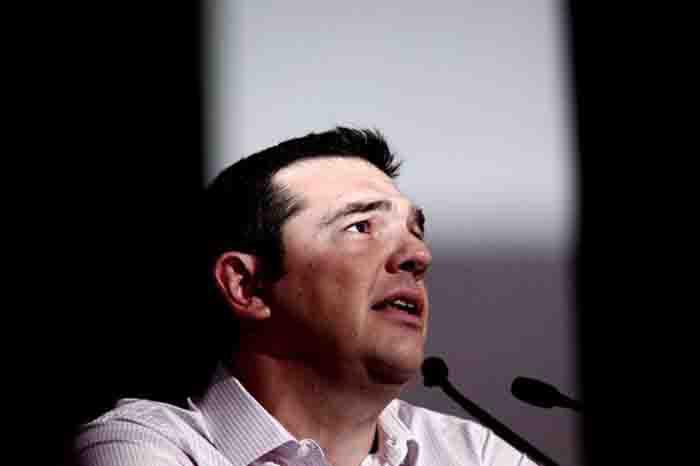

Consequently, the government of Prime Minister Alexis Tsipras (who resigned August 20) is being questioned after adopting the brutal measures demanded by the EU just hours after 61% of Greeks voted against them, casting NO votes in a national referendum.

The impact has been so strong that analysts have begun to ask if the new Siryza government, led by Tsipras, really intended to take up the battle against EU extortion, regardless of the ultimate consequences.

What is certain is that the Greek parliament, after a series of bitter discussions, a number of dissensions and resignations of public officials, opted to take the ‘unionist’ pill, evidence which for many experts indicates what German economist Wolfgang Münchau described as “the return of Europe to the power structure of the 19th century and the beginning of the 20th, when the strongest subjugated the weak at will.”

This is a well-founded conclusion, above all when one recalls the torrent of threats and demands which provoked disagreement between EU powers and Greek authorities, and the absolute insistence of German Chancellor Angela Merkel on an extremely austere policy, before considering any of Greece’s concerns.

In a few words, nothing remains in practice of the proclaimed principles of reason and cooperation which were supposed to govern the European Union, reduced at this point to a privileged club of decision-makers, who annul and disregard the opinions and demands of less powerful members.

This is the antecedent, as Wolfgang Münchau proposes, to the disaster awaiting an allegedly “pro-European” entity which preserves only its geographic location and the conceptual vacuum of its worn out name.

For Greece, in the meantime, the coming days will surely bring more internal conflict as the EU demands are implemented, even as its highest ranking authorities, with Tsipras in the lead, insist that if the agreement is bad, it could have been worse, and that the country still has an opportunity to overcome the crisis which has again been prolonged.

The current situation is also taking its toll on the hopeful image which at one time the new Greek leadership projected. Those who voted NO to the UE extortion, just a few days ago, have every right to feel deceived and frustrated that their opinion seemed to matter little in the final hour.

Moreover, given the Greek experience, new political forces in other European countries have been given a clear lesson on the intransigence and guile of an opponent from which they can only expect a thirst for revenge if they dare to challenge any dictate from the EU powers that be.