For Arthur Schopenhauer, the philosopher, happiness was nothing but a fallacy and we could only, as human beings, try to be as unhappy as possible. Do not have great expectations, the German depressive prescribed.

With peace it would seem that almost the same thing happens. Peace, paradoxically, has always been a conflictive issue for humanity, at least since memory found ways to perpetuate itself or left clues to be rescued.

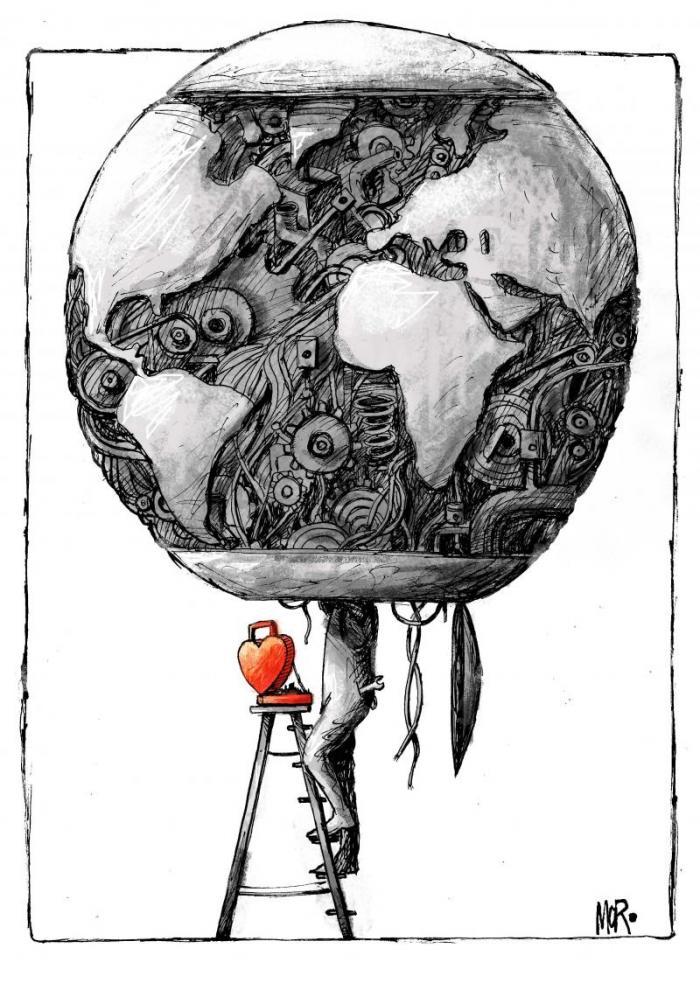

From the perceptible fractures in fossilized bones, the cryptic paintings on cave walls, the ancient writings of dead languages or buried cities, the history of humanity that we are getting to know could be understood as the history of our violence, intertwined, of course, with the old dream of getting out of it.

Peace, as a concept, has been so closely linked to violence that, when looking for definitions, the first thing that appears is the construction of the word as a sort of antonym par excellence. Antonym of war, conflict, noise or disturbance.

It is as if we do not know what peace means and what we do not want it to be. This only serves to define that peace, at the very least, is a search, a question and a dream.

However, memories deserve to be re-signified, because it is from the understanding of memories that the words of today take shape and make sense. And to memory, as we have already said, peace has been so elusive, so expensive, that we may be condescendingly invited to assume as normality, as “peace”, what, paraphrasing Schopenhauer, would be the least possible violence.

That is why we need to defend our right to redefine what we understand and want by peace or even to redefine what is war, conflict, noise or disturbance... or if Schopenhauer himself wakes up, to refute his sad understandings about happiness, because for us being at peace is not necessarily an antonym of struggle and necessarily a synonym of being happy.

Our idea of peace seems a little like García Lorca's, for the Spanish poet dreamed of singing it as a song under the olive tree: It will say: peace, peace, peace, / among the trembling of knives and melons of dynamite; / it will say: love, love, love, / until the lips turn silver.

Our idea of peace is necessarily like Rafael Alberti's when he longed for Peace without end, true peace, / Peace that rises at dawn / and does not die at night.

There are those who ask for too little when speaking of peace. There are those who try to cloister it in legal frameworks without even having achieved it and they go that way... as we in Latin America were - 200 years ago and it still weighs on us - prisoners of an idea of republic that we never had and never will have. It has been very hard for us, it is hard for us, to understand our capacity to have a voice and vote in history.

When they ask for peace in the world, we are not going to remain begging for 45,000 human beings not to be murdered in Palestine in the next 16 months. We will not be “little angels” from an ecclesiastical choir narrating with exclamations the tragedy in pursuit of a plastic peace that is understood as “not a shot is heard; no bombs fell today”.

We want a little more than that, precisely so that there will never be 45,000 more. We want a peace that does not resemble alms, because we already know that alms were never enough to kill poverty, but only enough for hunger and only for one day.

We do not want an ethereal peace that blurs, ours has conditions, circumstances and counter-narrative.

We do not want a peace of white doves that do not even resemble us; in our peace there fly cobblestone, black, mosaic, blue doves... and even the crows that refuse to go around pecking out eyes.

When they ask for peace in the world, we will not only be shouting for an end to war, we will also be shouting something like “Homeland or Death!” in Burkina Faso, and expelling from Africa, in general, the guarantors of a peace that starves us to death. We will be in a land seizure led by peasants in Latin America or conspiring with the mapuches.

When they ask about peace in the world, we will wonder about everything we do not know or understand about what is happening in the world... and we will run to study a little more, to feel a little more.

When they ask about peace, we will go back to the Greek myth of Sisyphus, to say that among those “punished by the gods” there is no peace possible; that in the torture of climbing every day the same sterile stone to the mountain, without will or awareness of what it is for, there is no peace either: we do not guarantee it.

Albert Camus, French writer, called us to imagine a happy Sisyphus and told us that “Sisyphus, proletarian of the gods, impotent and rebellious, knows the full extent of his miserable condition: he thinks about it during his descent. The clairvoyance that was to be his torment consummates at the same time his victory. There is no destiny that is not defeated by contempt”.

When they ask, we will say that Sisyphus was never happy and that, as it happens with tenderness, contempt is not enough either.