Roberto Fernández Retamar was, is, and will be essentially a poet. More than once he confessed that poetry had given him a reason to live. With poetry he reached his great passions: Martí, Cuba, Our America, the Revolution, family, love, the best of humanity.

Only a poet could say, almost at the end of his existence, in an essay on the occasion of the 60th anniversary of the triumph of the Cuban Revolution: “Let us trust in hope again, which according to Hesiod was all that was left in the glass, detained on the edge, when all the other creatures were gone.”

In other convulsive times, both Romain Rolland and Antonio Gramsci addressed the skepticism of intelligence, which they countered with optimism of the will. Years ago, I thought of adding: confidence in imagination, that essentially poetic force. “History,” said Marx, “has more imagination than we do.”Roberto was never out of tune with history, that is, with the time and place in which he grew and acted. He was already a prominent, young intellectual when he gave himself fully to the task of building a new country. The foundation of the Union of Cuban Writers and Artists, the university, diplomacy, work in the Casa de las Americas, illuminated by Haydée, the Center for Martí Studies, political tasks, membership in the Party, the founder of magazines, the lover of trova and baseball, the home shared with his essential Adelaida and their daughters - all together making for a coherent and consistent man.

He was born June 9, 1930, in Havana, where he was particularly attached to La Vibora, the neighborhood in which he was raised. He always said he felt “Viboran.” In a school book, he discovered Julián del Casal, and this reading influenced the vocation that was from the beginning encouraged by this access to the poetic mysteries José Martí. He began to write as an adolescent, and published his first verses 1948, in the Mensuario magazine.

In 1950, Retamar chose as his anthem, the poem edited in four parts by a man who would become one of Cuba’s great filmmakers, Tomás Gutiérrez Alea, indicative of another key to his lyricism: devotion to historic memory. The composition is dedicated to Rubén Martínez Villena.

Around 1951 he began to collaborate with the magazine Orígenes, a connection that would - in the future - link him to two exemplary admirers of Martí, like him, Fina García Marruz and Cintio Vitier. While he was studying Philosophy and Letters at the University of Havana - where he would for many years give classes and be recognized as a meritorious scholar - the news arrived that he was awarded the National Prize for Poetry, for his notebook Patrias. He traveled to Europe in the mid 50s for post-graduate studies and taught at Yale, in the United States,

In the meantime, his book of poetry Alabanzas, conversaciones was published in Mexico, welcomed by Retamar’s colleague Luis Marré with these words: “Roberto Fernández Retamar has achieved his purpose in these poems, that of an honest poet, who canbe nothing other than pure and disinterested, nothing short of someone to be read with respect, from the first poem to the last.”In 1959, his poetic work expanded and he assumed a new commitment to the Revolution. He published En su lugar, la poesía and Vuelta de la antigua esperanza, a prelude to a prodigal decade in which he added other poems: “Historia antigua,” “Con las mismas manos,” “Buena suerte viviendo,” and “Que veremos arder.” His combative and solidary experience with the Vietnamese people was reflected in Cuaderno paralelo.Over the years, until very recently, his production was voluminous, published in Cuba, translated into some twenty languages and recognized throughout the world, especially in Latin America and the Caribbean. One way of trying to approach this vast work is through anthologies such Algo semejante a los monstruos antediluvianos (1948-1988), Antología personal (2004), and Una salva de porvenir (2012). He became an essayist and literary theorist who established standards with La poesía contemporánea en Cuba (1927-1953) and Idea de la estilística, while extending his range Ensayo de otro mundo and Para una teoría de la literatura hispanoamericana.Other important titles in this field are Algunos usos de civilización y barbarie, Ante el Quinto Centenario, Nuestra América: cien años, and others approaching Martí, Recuerdo a…, En la España de la eñe, Cuba defendida, and Pensamiento de nuestra América. A selection of his essay work can be found in Para un perfil definitivo del hombre.

-II-

To introduce a compilation of Roberto's texts about Our America, Argentine political scientist Atilio Borón said: “Fernández Retamar, poet, essayist, and thorough explorer of all the recesses of our culture, illustrates with his life and his work the permanent validity of a social category that the dominant interests and intellectual trends of our time have attempted unsuccessfully to erase from the face of the earth: that of the critical intellectual.”Indeed, this dimension of the writer is not only present in his every word and action, but is also a paradigm of the revolutionary intellectual he advocated.When reviewing his essays, I pulled out Caliban (1971) and the volume of complementary works that he developed over many years on the subject, since in the opinion of many, the core of his contribution to decolonizing and anti-imperialist thought is concentrated here, along with his many passionate texts on José Martí.For the Argentine philosopher Néstor Kohan, this essay offers “an enthusiastic defense of the militant intellectual, not simply critical or merely committed, but an organic part of the revolutionary emancipatory movement. This is was precisely what José Carlos Mariátegui and Ernesto Che Guevara were; no different from Simón Bolívar and José Martí, or José de San Martín and Mariano Moreno.”And to leave no doubt about the validity of the concept, he notes: “The most disruptive, iconoclastic, and even shocking aspects, which a careful reading of this essay allows a reader, man or woman, of the 21st century to glimpse, were not errors, blunders, or Roberto's personal exaggerations. It was the Cuban Revolution as a whole (...) intent upon defying the canon of official culture and standards customarily tolerated within the confines of the politically correct, violating in theory, and in practice, the view of sticky pseudo-pluralism and well-informed, progressive thinking with which, still today, it continues to suffocate, neutralize and crush all radical dissent. In the 21st century, this task, no matter how exaggerated it may sound, or the tension it creates, remains pending.”

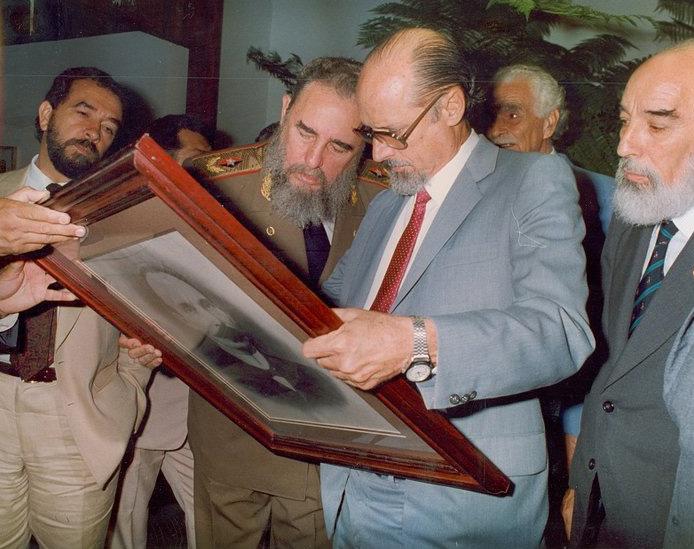

Is it necessary to insist that Roberto held Che’s thinking in his marrow, that he felt Che’s presence every day? Or that his way of fighting with ideas was always driven by the example of Fidel who he interviewed for the first time during his university years, and described as “a restless, combative youth, to whom a line from Martí could apply: In favor of whom will I devote my life?”

-III-

“Roberto Fernández Retamar is one of the most significant poets of his generation. He is very Cuban, shaded by the tree that challenges the universal tree of knowledge. Etched in him is the joy of marching in step with the rich destiny of Cubans, the best Cubans, who are universally unpretentious.” This is how he was described by José Lezama Lima, who observed his promising poetic career.

With Retamar, colloquial poetry reached an indisputable height among us. In his poems, characterized by the utmost rigor, there is a bit of everything and something for everyone. Readers can put together their own personal anthologies. Right now it occurs to me to revisit “Felices los normales,” because of its humanism; “Los feos,” showing the other side of beauty; or “Con las mismas manos,” a unique approach to the everyday within a transformative revolutionary mindset; or the divine “Oyendo un disco de Benny Moré,” to keep on mind as the centenary of this great musician nears.

But I am also moved again by “Y Fernández,” an evocation of the paternal figure who qualifies as one of the great heroic texts of our times.

And we will always need to return to the lines written January 1, 1859, entitled “El otro.”

We, the survivors/ To whom do we owe our survival? / Who died for me in the ergastula? / Who took my bullet? / The one meant for me, in his heart? / Upon whose death am I alive? / His bones left within mine, / His gouged eyes seeing / Through the look on my face, / And the hand that is not his hand / That is not mine either / Writing broken words / Where he is not present, in the survival.

We will all be present in Roberto’s survival. Those who were his contemporaries and those who turn to him tomorrow.