As soon as Alicia Alonso heard that the tyrant-president of Cuba had been overthrown by the Rebel Army, she wanted to return to Havana from the United States, a country where she had won artistic recognition, but she could not do so immediately.

“Precisely on the January 1, 1959, in Chicago, I had committed myself with the comrades of the revolutionary movement to go to a television studio, and tell the audience about the danger posed to Cuban youth, given the increase of repression by the soldiers of Fulgencio Batista, whose criminal practices were escalating as the regime lost ground,” the outstanding artist recalls half a century later.

"I was ready very early in the morning when someone told me, “Batista fled, the rebels are in Santiago, the dictatorship is done. I felt something very big inside, as if I were carrying all of Cuba in my chest.”

With Alicia the conversation flows smoothly. She answers quickly every question, but knows how to give weight to her words. If she needs to check a piece of information, she verifies it with her companion, Pedro Simón, a renowned literary critic and researcher, currently director of the Dance Museum. The only difficult thing lies in the impossibility of capturing, in a written interview, the movement of Alicia's hands. Many of her comments are accompanied by gestures, accents, and body language with which she emphasizes or qualifies a comment. She has an exceptional memory.

- When could you finally return to the country?

–January 11th. I regretted not being able to witness the entrance of the rebels into Havana. But I knew the homeland was freed, so I packed my bags to leave as soon as I had the chance.

- Did you know, at that time, that a new era was beginning for your people, and in particular, for your artistic future?

- I was confident that something good and big would happen. I want to tell you that even before the Rebel Army defeated the dictatorship’s forces, we sent the rebels in the Sierra Maestra, a far-reaching proposal of what ballet could become in the days to come. The bearer was a friend of ours and a great lover of dance, a very cultured and at the same time very revolutionary man, Dr. Julio Martínez Páez, who earned the rank of Comandante in the mountains.

- In 1956 you said goodbye to your audience on the island. You said you would not dance here anymore until the political situation in the country changed.

- It was a position of principle, not only mine, but of all my colleagues. Batista, through a man who ran the official culture institution, wanted to take advantage of the prestige of the Ballet of Cuba, which I headed, to try to improve his government’s bad image. They wanted to pressure us, depriving us of a ridiculous state subsidy. And he offered me, individually, and since the public respected me a great deal, a kind of life pension. Since I didn't fall for that, he withdrew the grant. Actually, the man who ran that institution, Guillermo de Zendegui, a man who appeared to be extremely polite, said that I had a terrible defect: I was a communist.

–Let's go back to 1959. The Revolution triumphs and you begin your career with us. Under what conditions?

- The effervescence of those initial times quickly reflected in our work spirit. In addition, I had the joy of seeing the dream of placing ballet as one of our most important cultural expressions - in the new reality under the Revolution - became reality very quickly.

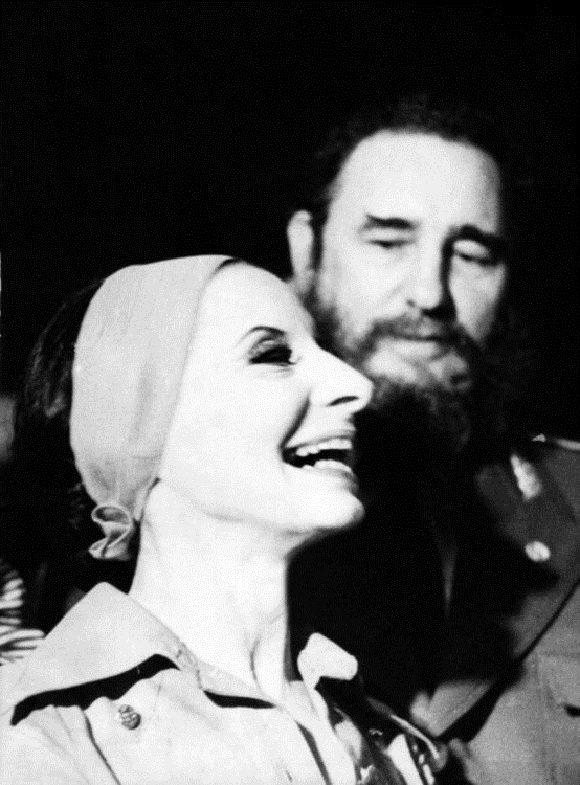

- What role did Fidel Castro play in this?

- In 1959, Captain Antonio Núñez Jiménez arrives one day and tells me: You have a visitor. It was Fidel. It was incredible to me that in the midst of so many things to do, the Comandante would find time to spend with us. He immediately got to the matter at hand and told us what we needed, and gave us all his support. Fidel is an exceptional being; he quickly supported our ideas and enriched them. From the first meeting I had with him, I realized that Fidel understood the importance of artistic culture, and particularly of ballet, for the Revolution and got many, even us, to better understand that idea.

- Can it be said that, at that moment, the idea of a Cuban Ballet School began to come true?

- That idea was always in our spirits, practically since I began dancing, and then, as of October 28, 1948, when we founded the company that is named the National Ballet of Cuba today. Sixty years is a short time in history. The incredible is to have done so much in such a short time. Imagine what this means; a small island, which inherited underdevelopment, with a school recognized throughout the world. And then, the fact that it is not a school for an elite, but for an entire people, with teachers and dancers who come from that people and a wide and diverse audience. Hey, this is fabulous, it doesn't exist anywhere else, I can assure you! Now, the truth must be said: the School is the work of the Revolution.

- How do you ensure the continuity of this work?

–The Revolution has created a system of artistic education in which ballet has a special place. We have developed a dance pedagogy that is highly regarded in the world. Young people who have talent and work hard have the opportunity to accomplish great things. And today we have a great facility, the National School.

- How do you assess the international impact of the School?

- In Latin America, it has been enormous. There are many students who have come to us and continually ask us for teachers.

- What have you been obliged to fight, to make way for your concepts about dance?

- At first, in the United States, Latinos bore the stigma that they were only fit for folkloric dance. I met people who said that our bodies were not good for classical dance. Those prejudices have been left behind. And I don't speak only of Cubans, in Latin America and Spain great dancers have emerged, as well. I’ll tell you more; the prejudices even included U.S. dancers. It was thought that only by being Russian, or in any case, European, one could excel at ballet. There were even those who changed their last name, to pass as Russian.

- As a dancer you have left a legend in your wake. But you are also a respected choreographer. How do you assume creation in this field?

- I always liked to create for the stage. Even in my time as a dancer, I cultivated that vocation. I see the complete choreography inside me. I explain to my collaborators not only the movements, but how I conceive the stage, the gestures, what I intend with each of the elements that come into play on the stage. I dance with my choreographies; it is a way to keep dancing. I always enjoyed dancing, today I do it through others. And I swear I am following and feeling every movement, the emotions of each character. At the end of a performance, I end up exhausted, as if I had been on stage all the time.

- Would you like to give examples of how the creation process unfolds? Let's say, based on Lucia Jerez, the novel by José Martí.

-That ballet was dedicated to celebrating the 400 years of Cuban literature. Therefore, we were obliged to start from an original literary work, and nothing better or more challenging to do so than a work by Martí, his only novel (...). It is an exciting story that, on the other hand, had a libretto for ballet written by no other than Fina García Marruz, who I consider one of the greatest Cuban poets. That script was a starting point, with a very sensitive poetic touch, which had to be translated into the language of movement. A young collaborator, José Rodríguez Neira, in turn, made a version of the libretto with which we set to work, so that Marti’s novel came to life in the dance, giving meaning to the gesture. At the same time, we had to look for music that suited the choreography, and looking for it, I found a score by Enrique González Mantici, a very important composer and conductor, already deceased, who we admire. And I discovered that it seemed to have been written specially for the work.

- Does the aggressive attitude of U.S. administrations towards the Cuban Revolution affect you personally?

- I believe as much or more than our people, that the main victim is the U.S. people (...). When I addressed a letter to U.S. artists and intellectuals, I did not expect it to engender such a broad and rapid response. I think it helped raise awareness about the need to relaunch cultural ties based on respecting our right to exist, to choose our own destiny. I know that is not enough, but at least it opened a door.

- Do you feel proud of living in Cuba?

- Immensely proud. Especially for sharing the sense of dignity. Here we work to serve the country, to grow as human beings, amidst great difficulties, but with full confidence in the future.

- At this point, what do you expect from life?

- Everything!